I graduated from Stanford in the Spring of 1970. In my entire life, I had never felt more relieved. Behind me, it seemed, was an entire life of forced study. Somehow, not real life, but the preparation for real life. I had a very confident, almost giddy, sense of the world stretching before me, with all its many wonderful opportunities. The incredible historic time, the amazing renaissance of art and thinking, that was happening, with San Francisco seemingly the world epicenter; all of this fed into the excitement that I felt. Any one who lived there at the time, would testify to the unique energy field that seemed to be in the air. The sense of liberation that I experienced was overwhelming. This was “The Sixties”, even though it was already 1970.

The week previous to graduation, I had purchased my first automobile. It was a 1959 Mercedes 220S sedan that had been slammed so hard in a rear end collision, that the left rear tail light now occupied a position directly below the rear window. Apparently, whatever the car had hit, or had hit the car, had somehow missed or skipped over the rear axle, and the left rear wheel extended out a full eight inches beyond the nearest crumpled sheet metal of the bodywork. The frame, after all the crunching, had remained remarkably straight. I had passed the car, slumped on its deflated rubber, in a student parking lot, for an entire year as I came onto campus from my lodgings each morning. I contacted the owner, was assured that, yes, the engine ran, and, yes, it could still roll. We agreed on a price of $50. What was left of the interior was quite cushy, leather seats, real wood trim and that alluring luxurious Mercedes emblem in the middle of the horn button. I experienced imitations of luxury. I limped the car home on four of its six cylinders and, later that day, was able to get them all firing.

The week previous to graduation, I had purchased my first automobile. It was a 1959 Mercedes 220S sedan that had been slammed so hard in a rear end collision, that the left rear tail light now occupied a position directly below the rear window. Apparently, whatever the car had hit, or had hit the car, had somehow missed or skipped over the rear axle, and the left rear wheel extended out a full eight inches beyond the nearest crumpled sheet metal of the bodywork. The frame, after all the crunching, had remained remarkably straight. I had passed the car, slumped on its deflated rubber, in a student parking lot, for an entire year as I came onto campus from my lodgings each morning. I contacted the owner, was assured that, yes, the engine ran, and, yes, it could still roll. We agreed on a price of $50. What was left of the interior was quite cushy, leather seats, real wood trim and that alluring luxurious Mercedes emblem in the middle of the horn button. I experienced imitations of luxury. I limped the car home on four of its six cylinders and, later that day, was able to get them all firing.

With a friend in the passenger seat, we headed out to the Bayshore freeway for a test drive. We pushed it past forty miles and hour, past fifty miles and hour, past sixty miles an hour and were approaching seventy when the front hood latch released and the hood of the car flew up in a solid wall, totally blocking our forward vision. The hood in fact wrapped entirely over the roof. I eased on the brakes and attempted to steer looking out the side window. Do not try this trick. Mercifully, I was able to maneuver over to the shoulder. The two of us stood on top of the engine and managed to reef forward on the hood such that when it was somewhat near its original location, we were able to climb up on top of the hood and jump up and down to crush it even closer to home. We finished the job with a stout piece of rope from the back seat, and limped homeward, damaged but undaunted.

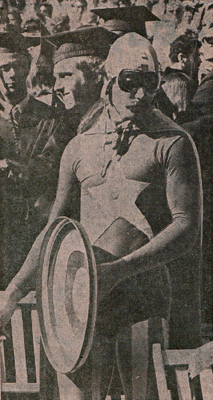

In order to wholly partake in the spirit of those heady times, and to fully celebrate my own graduation, in the most expressive and enjoyable fashion I could imagine, I put together a costume mimicking the Captain America comic book hero, complete with the emblematic round shield. I wore this to my graduation ceremony.

The day previous to my graduation, I donned my new garb, and stuck out from Palo Alto hitchhiking. It was a sign of those Hippie Halcyon days, that I could hardly put out my thumb before some smiling car load of hippies would screech to a halt, to have the privilege, of helping out Captain America. I hitchhiked out to the coast, up past Half Moon Bay, on through San Francisco, down the Bayshore and back to my home, having hardly wasted five minutes waiting for a ride. Oh, what fun it was, to travel through the world as an alter ego, safely hidden behind my all protecting mask, always keeping it in place, something of absolute importance to any masked super hero. I was never seen as Tom, I was only Captain America.

The carefully sewn costume had a remarkably visual vividness to it, with the skin tight lycra in bold, red, white, and blue. In a visual field a quarter of a mile away, there was no way that the costume would not stand out like a beacon. By walking through the world inside the mask, you observed the instant attention of all within range. Most broke into spontaneous smiles as if an amiable clown had suddenly crossed their tracks, and indeed that was entirely the case. I felt myself the absolute soul of wit, and it seemed as if at every challenge I was able to leave the scene with all players smiling. I smoked some sweet flowers, early in the morning, and then spent the entire day of graduation walking about the Stanford campus, within my costume.

Remarkable as it seems now, I had most definitely caught the flavor of the day perfectly, as the distribution of the A.P. wirephotos was to attest. I received, later, newspaper clippings from Japan to Florida. The image had travelled world wide. I made the front page of my own local ‘Seattle Post Intelligencer’, which did not note that the masked man in the photograph, shaking the hand of the Stanford President, was a native son.

Everyone, on that day,wanted to be photographed, with their caps and gowns, with Captain America. At the ceremony, a long line of graduates snaked its way up to the stage to receive their diplomas. As I was clearly visible, the crowd was well prepared when I emerged on stage to shake the hand of the college president amid a roar of cheers. The laughter and mirth that accompanied Captain America, not me, on that day, will bring a smile to my lips when ever I recall. But the good vibrations were not just at the graduation, for it seemed as if everyone you saw on the streets back then, was smiling, with a knowing twinkle in their eye. Ahhh, the sweet flush of youth.

Everyone, on that day,wanted to be photographed, with their caps and gowns, with Captain America. At the ceremony, a long line of graduates snaked its way up to the stage to receive their diplomas. As I was clearly visible, the crowd was well prepared when I emerged on stage to shake the hand of the college president amid a roar of cheers. The laughter and mirth that accompanied Captain America, not me, on that day, will bring a smile to my lips when ever I recall. But the good vibrations were not just at the graduation, for it seemed as if everyone you saw on the streets back then, was smiling, with a knowing twinkle in their eye. Ahhh, the sweet flush of youth.

I left the stage that day, waving to the crowd. Then I left Frost Amphatheater, and still relishing my five minutes of fame, I climbed on my bicycle and rode home. I packed up the crumpled Mercedes and prepared to leave Stanford behind. I half assumed that I was somehow, also, irrevocably burning my academic bridges behind me. I guess this proved to be true, because I never looked back. But, ahead, I saw a whole new fork in the road, and this felt fine.

Two days later, the back seat of the Mercedes loaded with all my worldly possessions, I struck off, headed north, for an entirely new chapter of my life. Never before, or since, had I felt so liberated. The world was now my oyster, and I could barely wait to devour it.

The rear bodywork of the car was so crumbled and twisted it appeared as if it might have been a gigantic wad of crumbled paper. On this surface I had painted with red, white and blue paint, a perfect semblance of a rippling American flag. These were the heady and glorious sixties and exuberance seemed uncommonly welcomed by the man on the street. Many who I encountered on the highway yelped their support and flashed the ubiquitous peace sign, while some sad few, scowled at me, with red neck hatred. Any of these might have displayed the popular blindly loyal bumper sticker, proclaiming “America Love it or Leave it.” It too was ubiquitous. My bumper sticker would have read, “America, Love it or Change it.” Such were the times.

When I arrived back in Washington state, I wound up moving into a tent on Vashon Island, where my brother, Gary, and I had purchased four acres in the middle of the woods, at the end of a long dirt road, the previous summer. Over the next year the tent evolved into a driftwood and tar paper shack, that was to become my own first home in the World. Gary and I had pooled all of our money, saved from several years of odd jobs to come up with the $4,000 purchase price. There was no water, no electricity, but there was freedom in abundance. I was happy in my shack in the woods. I relished it like nowhere I had ever been. I soon found various employment on the island and met many other refugees from the city, who had moved to this rural location to try to return to the garden, and live off the land. This seemed the common objective of an entire wave of long haired, home spun visionaries who arrived collectively on the island during those years. Everyone shared and helped each other in any way they could to try to start their new lives. Many were still living there forty years later, tending their grandchildren. It was an incredibly special time and community, and I wound up staying there for most of the next ten years.

When I arrived back in Washington state, I wound up moving into a tent on Vashon Island, where my brother, Gary, and I had purchased four acres in the middle of the woods, at the end of a long dirt road, the previous summer. Over the next year the tent evolved into a driftwood and tar paper shack, that was to become my own first home in the World. Gary and I had pooled all of our money, saved from several years of odd jobs to come up with the $4,000 purchase price. There was no water, no electricity, but there was freedom in abundance. I was happy in my shack in the woods. I relished it like nowhere I had ever been. I soon found various employment on the island and met many other refugees from the city, who had moved to this rural location to try to return to the garden, and live off the land. This seemed the common objective of an entire wave of long haired, home spun visionaries who arrived collectively on the island during those years. Everyone shared and helped each other in any way they could to try to start their new lives. Many were still living there forty years later, tending their grandchildren. It was an incredibly special time and community, and I wound up staying there for most of the next ten years.

At the end of my first summer in my tar paper shack, which offering minimal protection against the coming winter, I looked for other options. Early in the fall before much snow had dropped on the pass, I drove into the Cascades to check out a new ski area that had just been built. They were looking for workers and I signed on for construction and for a position operating the chair lift once the ski season started. In retrospect, it seems amazing to me now that the entire ski area was run by people not out of their twenties. Except for a few gnarly old mechanics who kept the machinery running. It turned out to be a record snow year, and since nothing at that point in my life was more important to me than skiing, I was in heaven. Everyone on the lift crew and all the ski patrol smoked marijuana daily, yet we managed to run the area without a hitch. It was an amazing time which never recreated itself afterwards. I wound up working at the area for two years. In the spring of the second season while attempting to land a fifty foot jump, I misjudged my landing and crushed a disc in my lower back. I was laid up in bed for several months before I finally succumbed to spinal surgery. The better part of the next year was spent recovering. The event shattered my youthful illusions of immortality. In more ways than one, childhood’s end was lurking around the corner. The permanently injured spine was a lasting memory of youthfull folly.

At the end of my first summer in my tar paper shack, which offering minimal protection against the coming winter, I looked for other options. Early in the fall before much snow had dropped on the pass, I drove into the Cascades to check out a new ski area that had just been built. They were looking for workers and I signed on for construction and for a position operating the chair lift once the ski season started. In retrospect, it seems amazing to me now that the entire ski area was run by people not out of their twenties. Except for a few gnarly old mechanics who kept the machinery running. It turned out to be a record snow year, and since nothing at that point in my life was more important to me than skiing, I was in heaven. Everyone on the lift crew and all the ski patrol smoked marijuana daily, yet we managed to run the area without a hitch. It was an amazing time which never recreated itself afterwards. I wound up working at the area for two years. In the spring of the second season while attempting to land a fifty foot jump, I misjudged my landing and crushed a disc in my lower back. I was laid up in bed for several months before I finally succumbed to spinal surgery. The better part of the next year was spent recovering. The event shattered my youthful illusions of immortality. In more ways than one, childhood’s end was lurking around the corner. The permanently injured spine was a lasting memory of youthfull folly.

About this time, near the summit of Snoqualmie Pass a large, state highway warehouse, that dated back to the Roosevelt New Deal Work Projects, was demolished to make way for a new highway. Using a rental trailer hitched to my ’61 Chevy pickup, I was able to acquire and transport a substantial stash of building materials back to Vashon Island, where I was planning to expand my tar paper shack into a more permanent structure, a real house. I had little real house construction experience, but I had watched my father use tools my whole life, and had often helped him. He was a remarkable cabinet maker, who had actually apprenticed as a wooden boat builder in his youth. He built a boat in our back yard when I was growing up. So I figured with hard work and paying attention, I couldn’t go too wrong, and I took courage in an old carpenter’s adage that: “you just have to be smarter than the hammer”. Undaunted, I set about the task of building my first house.

At about this same time, at the end of my second season at the ski area, I started dating Marilyn, my future wife. After about a year together, ‘Mer’ turned up pregnant and a whole new chapter of my life began to unfold.