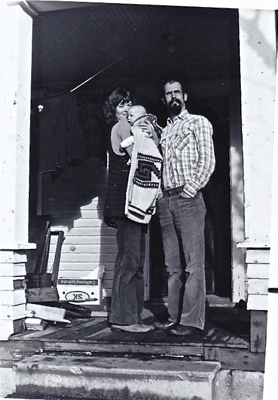

When Marilyn and I were living in West Seattle, in 1974, in our first house, I started a business doing hauling and cleanup. I put an ad in the Seattle Time that read something like this: ” ‘Tom’s Truck’, Hauling and Cleanup, no Job too Big or too Small. Best rates.” I was surprised at the number of responses that came my way. At the time, my truck was the same wrecked Mercedes Benz sedan that I had purchased for $50.00, to drive home from California, when I graduated from college. I had cut away the rear bodywork of the Mercedes with my cutting torches and had turned it into a flat bed truck. This I used on all of my first jobs. This particular model Mercedes, a 1959, 220S had big cushy leather seats and real wood trim on the dash board. I cut into the body work right behind the two front seats, built in a bulkhead, separating the cab from the bed, and used this rig as my utility vehicle for a number of years. Sometimes I would load the Mercedes, which I nick-named “Beyondus”, so mercilessly, that the independent rear suspension splayed out so far that the differential would hit the highway. It was a sight to behold, and I caught a lot of long looks, but in those days I was only too happy to laugh at myself, and my own joke.

When Marilyn and I were living in West Seattle, in 1974, in our first house, I started a business doing hauling and cleanup. I put an ad in the Seattle Time that read something like this: ” ‘Tom’s Truck’, Hauling and Cleanup, no Job too Big or too Small. Best rates.” I was surprised at the number of responses that came my way. At the time, my truck was the same wrecked Mercedes Benz sedan that I had purchased for $50.00, to drive home from California, when I graduated from college. I had cut away the rear bodywork of the Mercedes with my cutting torches and had turned it into a flat bed truck. This I used on all of my first jobs. This particular model Mercedes, a 1959, 220S had big cushy leather seats and real wood trim on the dash board. I cut into the body work right behind the two front seats, built in a bulkhead, separating the cab from the bed, and used this rig as my utility vehicle for a number of years. Sometimes I would load the Mercedes, which I nick-named “Beyondus”, so mercilessly, that the independent rear suspension splayed out so far that the differential would hit the highway. It was a sight to behold, and I caught a lot of long looks, but in those days I was only too happy to laugh at myself, and my own joke.

As business grew, I realized I needed a bigger vehicle. Outside a local boat yard, I had seen a 1947 Dodge Step Van. It had once been used by a local department store. The box of the body was quite spacious. I could stand up inside, and if I loaded lumber all the way to the front windshield, sixteen foot lengths would fit completely inside. With the rear doors open I could haul something close to 30′ long. It proved to be a great rig, a true ‘oldie but goodie’. When I first saw it, it was sunk down on its tires, covered with dirt, and had a meek ‘For Sale’ sign propped in the window. I knew that, I was in a good bargaining position. The agreed price turned out to be $150.00. But even this modest price was more than I had at the time. During this early stage of our marriage, I was routinely dumpster-diving for produce at local super markets, just to help put food on the table. Later that week, I received a telephone call from a woman inquiring what I would charge to drive a load of furniture to Modesto, California. I immediately said $150.00. She agreed. I returned to buy the truck.

When I went to meet the woman, I saw that the load of furniture would fill every square foot of the truck. It was then that she asked whether her and her sister could both accompany me on the trip. They both appeared to be in their mid-sixties and I questioned how smoothly such a trip might enfold. Mind you, at this point, I had driven the truck a total of about 10 miles. The round trip to Modesto would be about 1600 miles. It was a sketchy proposal all the way around. But, I tried not to let my apprehension show. I agreed that if they paid all fuel costs, they could drive with me.

We set the furniture such that one large arm-chair faced forward at the very front of the load. This would be just to my right as I sat in the driver’s seat. The only other seat was a small fold-down jump seat low in the right wheel well, just inside the door, not a comfortable location. The passenger in that seat could not even see out the windshield. As it later turned out, on the entire three day trip to Modesto, the same sister sat in the armchair and never once traded positions with the other sister. It seemed the type of relationship between them, that you might expect from two sisters, so lacking in social skills or even the most rudimentary of charms, that they are marooned in the world with only their own company. And it did not appear that they particularly enjoyed that company. Behind the three of us, in the truck, was a solid wall of their possessions, packed snug to the roof of the truck.

On the day of our departure I had driven barely to the edge of the Seattle city limits before I ran out of gas. The truck had no gas guage. I tried to reassure the two women that this was a minor set back. After running on foot to find gas and returning with a full can, I opened the engine cover which was inside the cab, just to my right, and just in front of the large arm chair. I primed the carburetor with a good slosh of gas, but when I fired the ignition the entire engine compartment erupted in flames. I quickly slammed the cover, which extinguished the fire, as the two women peered with alarm through the sliding passenger door. I assured them that this was no big deal, all the while envisioning the truck and its entire load of furniture blazing away on the shoulder of the road. On my next try I was able to get the engine started and we were soon on our way down the highway.

Within a few miles, however, I became aware that the truck had no front shock absorbers. This resulted in the front of the truck developing a bouncing up and down motion, as it picked up the rhythm of the sections of the concrete highway. It would get increasingly more exaggerated as I drove, and I tried to vary my speed, and even hit the brake pedal such that I might break up the cadence of the bumps. It must have looked strangely comical to an outside observer to see this truck pogo-ing down the the highway, but I knew that this was not a good situation. Nonetheless we managed 150 miles that first day and spent the night in Vancouver, Washington where the sisters had friends.

The next day, assessing the problem, I was able to install a set of shocks that I purchased from a local junk yard. That took the whole day. After sleeping in my now grimy, grease stained clothes, in my sleeping bag, the next morning we were on our way again with much improved steering control. Most of Oregon rolled beneath us without additional troubles. We were driving on what was then the practically new, and largely empty, Interstate 5 Freeway. We drove for about ten hours on that day. At pretty much every rest stop that we stopped at to relieve ourselves, I would surreptitiously slide into the woods to smoke a joint. This led to lively conversation with the two women, and it was an improvement on listening to their constant squabbling.

That night we all three slept in a single motel room, me on the floor in my sleeping bag, them snoring together in the same bed. The next day, again, went smoothly as the beautiful sunny California landscape rolled past us. At about nine o’clock that night while still light, we rolled into Modesto, and reached our destination, a second floor apartment outside the downtown area. I saw that it was to be my job to move every scrap of furniture up to that second floor. I was incredibly strong in those years, from weight lifting, running, and my high school wrestling, and I took the solo moving of couches, bureaus and tables as a physical challenge. It was not until the last scrap of furniture was in its place that the sister who had hogged the armchair the entire journey, finally coughed up my $150.00. With not so much as even a ‘thank you’, I was dispatched by the two ugly sisters, and happy I was for that to happen. On the return journey in the empty truck, the six cylinder Dodge flathead mill purred, and I flew over the pavement, back to Washington, often times reaching an awesome 70 miles an hour. The sweet cannabis wafted out the window into beautiful summer sunshine, and I was young and free, with $150 in my pocket, and life was good.

I used the same truck for 25 years of demolition work, and I tortured it in every conceivable way and it never stopped giving of itself, until it finally gave up the ghost in 1987. For years after that, I used to see it in the same junk yard just south of Hailey, Idaho. That truck, and the Mercedes flat-bed, and dozens of other cheap beaters that I bought and sold or kept and loved, made up an entire history of vehicles in my life.

I worked on all my own cars and trucks and motorcycles, throughout my life, and the long experience of wrenching on mechanical stuff, led to me formulating an entire philosophy of automobiles, and how they fit into our culture, and how the manufacturers have increasingly raped the unfortunate consumer, and how, despite the advertising campaigns, the cars we are able to buy have grown increasingly user unfriendly, and particularly hostile to the owner being able to perform his own repairs, or indeed anyone being able to perform the repairs. I am describing ‘planned obsolescence’ as one of the most insidious and evil trends of the modern human experience. (One need look no further than the meager trickle of useful information provided in a typical ‘Owner’s Manual’, to get a partial idea of what I’m describing. ) The way in which useless machines and products have worked there way into our modern life, and the extent to which our manufacturing capabilities, and natural resources are squandered as a result, was to become an important part of what I hoped to express in my life as an artist. More on this ‘Manifesto of Bogus Manufacturing’ later.